According to a Colombia University study, in 2022 nearly one in ten US residents over the age of 65 suffers from dementia. Think about that for a minute, then count the number of retired people in our neighborhood.

…almost 10% of U.S. adults ages 65 and older have dementia…

We definitely have more than ten people in the neighborhood over 65, so it follows that some of us suffer from dementia, right?

Um…not necessarily. First, statistics don’t work that way. Second, dementia rates scale non-linearly as age increases, and most of us are at the lower end of the 65-to-death range. Third, we happen to live in a neighborhood whose population is predominantly financially secure and well educated. Luckily for us, rates of dementia among our cohort is low compared to the population at large.

Which doesn’t mean we can stop worrying, because we also tend to live longer, so will become more likely to suffer from dementia as we grow older. Unfortunately, statistics do work that way.

About now you might be asking, “Why is she writing this downer post?”

Obviously because of Mendeleev and the Virginia Memory Project.

Mendeleev and the Periodic Table of the Elements

Mendeleev was a Russian chemist who, in 1869 proposed a chart of the elements ordered by atomic weight, and grouped by similar reactive properties. For most of us, unless we study chemistry, the story begins and ends there. But the story actually goes both backwards and forwards from that point.

Backwards because Mendeleev was not the first chemist to propose grouping elements into a table. From Aristotle onwards, scientists have been working on elemental categories. The time was right for Mendeleev’s proposal because advances in experimental chemistry accelerated in the 19th century, with a wealth of discoveries fueled by improved scientific equipment.

Nor did Mendeleev develop his theories in a vacuum. Chemists Antoine Lavoisier, Johann Wolfang Döbereiner, John Newlands and Henry Moseley put forth models. In fact, not long before Mendeleev proposed his grouping, John Newlands also tried to publish a table of elements ordered by weight and grouped by similar reactive properties. Newlands’ paper was rejected because of a fatal flaw: he did not leave room for undiscovered elements in his table. Similarly, Moseley’s model wasn’t adopted because he proposed his table without making any predictions, a necessary feature in experimental science. Unlike these predecessors, Mendeleev left holes in his table for as-yet undiscovered elements, and used the table to predict features and behaviors of these elements when and if they were discovered.

And now we remember and celebrate Mendeleev because most of his predictions, whether they were ‘missing’ elements, or properties of those elements, were supported by later experimental results. His table continues to be useful to chemists over 150 years later.

And now you are all probably scratching your heads and wondering, “What does this have to do with dementia?”

In a word, data.

Mendeleev and other chemists of the 19th century had access to decades of experimental results in which they could search for patterns and propose theories. This is true for science in general. The first step in applying the scientific method depends on data collection. Chemistry, physics, geology, AI LLMs,… and medical research, all depend on getting lots of data.

But these mountains of data don’t yet exist for scientists studying progressive dementia.

What is Dementia?

I’m getting ahead of myself, so let’s back up. First, keep in mind that I am not a medical professional. If you have specific questions about dementia and your health or the health of a loved one, please discuss these questions with a qualified health care provider.

Meanwhile, let’s be clear that dementia is not a disease. It is a group of symptoms whose cause may be many and varied. Consider the upper respiratory infection. You cough, sneeze, have a sore throat, headache, and so on. These symptoms could be caused by a cold. Or perhaps the flu? Allergies? Maybe Covid? How about bronchitis? The symptoms are the outward manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

Dementia is not a disease. It is a group of symptoms whose cause may be many and varied.

The characteristic symptoms of dementia are difficulties with memory, language, problem-solving and

other thinking skills that affect a person’s ability to perform everyday activities. A bit mushy, I’ll admit. Every time I fail to solve the NYT mini in under a minute, I panic a bit. Forget why I entered a room? Panic. Tell an anecdote and then recall I’ve already told it before? Panic. Can’t remember the name of my favorite actor? (Kenneth Branagh, btw) Panic!

Regardless of how inconvenient and disconcerting these memory lapses are, at the moment they are not interfering with my ability to manage my life. Annoying and frustrating, certainly. But I can still pay bills on time, drive, remember important dates, recognize my neighbors, and find my way around metro systems in various cities.

For now, at least.

But if dementia is a set of symptoms rather than a disease, what causes these symptoms?

According to the Mayo Clinic, dementia falls into two broad categories: reversible and progressive. Reversible dementia can be caused by infections, endocrine problems, poor nutrition, medicinal side effects, brain tumors, etc. Once the root causes have been addressed, the problematic symptoms generally reverse. This is the good news.

Progressive dementia is another matter. These dementias get worse over time, and are not (as of now) reversible. Progressive dementia can be caused by a number of different diseases, the most common being Alzheimer’s. Unfortunately, the medical community does not yet know exactly what causes Alzheimer’s. Most patients have fibrous growths in the brain, but not all, and not every patient with such growths develop Alzheimers. In other words, there may be high correlation, but fibrous growths are neither necessary nor sufficient to cause the disease. Similarly, genetics play a role in some cases, but not all.

In a nutshell, the medical community does not know what causes progressive dementia generally, nor Alzheimer’s specifically. And unlike Mendeleev and his fellow chemists in the 19th century, scientists today don’t yet have enough data on which to base their research.

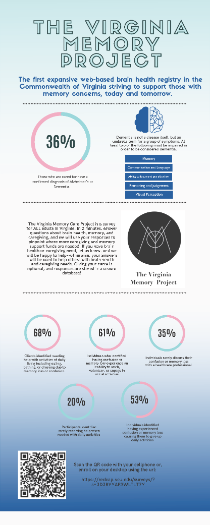

Which is why I want to introduce you to The Virginia Memory Project. Full disclosure: My daughter Ann is the director of the VMP.

What is the VMP?

The Virginia Memory Project was written into VA law last year. The law states that, “The purpose of the Virginia Memory Project shall be to collect and analyze data on Alzheimer’s disease, related dementias, and other neurodegenerative disorders in the Commonwealth…”

The website goes into a bit more detail. “The Virginia Memory Project is a survey for all adults in Virginia about brain health, memory and caregiving. It is the first expansive web-based brain health registry in the Commonwealth. Your answers will help policymakers and public health workers prioritize resources for people with memory loss and caregivers in Virginia.”

I want to stress “…all adults…” Because this survey isn’t just for those who’ve been diagnosed with dementia. And these data are not just for researchers. Our elected officials and policymakers need data to develop plans for managing the onrush of senior citizens within the state at risk for developing some form of dementia.

According to the VMP, citing the Alzheimer’s Association, 190,000 people aged 65 and older have Alzheimer’s within the Commonwealth of Virginia. The US Census Bureau estimates the population of VA to be about 8.7 million, of which 16% (1,392,000) are over the age of 65. After a bit of math magic we can conclude that around 13% of Virginia senior citizens suffer from Alzheimer’s. And keep in mind that this number doesn’t include dementia from other causes, and undiagnosed cases of Alzheimer’s. That’s a large percentage of the population for whom there is no hope of effective treatment, nor of a cure.

So I suggest we get a move on and help with the data collection.

What Can We Do?

Recall that the VMP is a survey. A survey open to all Virginia residents. According to the site, the data are anonymous, so you don’t have to worry about your personal information being released into the wild. As an added benefit, the VMP will refer you to organizations that can help if you yourself are suffering from, or are a caregiver for someone suffering from dementia.

So what we can do is add to the data so that policymakers can make data-driven rather than merely ideologically-driven policies and decisions. And so that researchers can have the data they need to start defeating this scary and tragic disease.

It may be too late for our generation to benefit from dementia research, but with enough data, research, and support, perhaps our children won’t have to face growing old with dread.

KAS

Bruce Sandkam

Chris Gareis